For Breaking Disaster

“Ingram has put her research to excellent use. As with other general histories, personal experience–human interest–looms large. Telegrapher Vincent Coleman, hero and victim, merits an entire chapter. Despite its richness and readability, I wanted for source notes or a comprehensive bibliography of printed primary sources. Yet the inherent interest of such accounts is undeniable; evidence derived from printed primary sources such as newspapers is always a valuable resource for any historical conversation.” -Barry Cahill, Atlantic Books Today

“It is not what any place on earth would want to be famous for, but until 1945 and Hiroshima, the explosion that occurred in Halifax Harbour on December 6, 1917, was the largest man-made blast the world had ever seen. And it was horrific in its aftermath…. Now, with the 100th anniversary of the explosion coming on Wednesday, a bevy of books has been released to mark the event.

…Ingram takes a different and refreshing approach. She’s fashioned a narrative using newspaper reports published directly after the blast. It’s an effective technique that keeps the pages turning and effectively chronicles the chaos and misinformation that spread far and wide. She devotes a chapter to the plight of Imo helmsman John Johansen, a Norwegian who some thought was a German spy responsible for the explosion. He had been carrying a letter “written in a foreign language” (German, the people thought, but actually Norwegian), which was enough to make him a target, a story that resonates today amidst racism toward people from Middle Eastern countries, and others. This is a terrific one-stop overview of the devastating human cost that was the Halifax explosion.” –James Macgowan, The Toronto Star

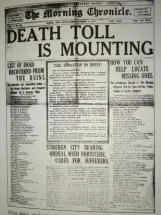

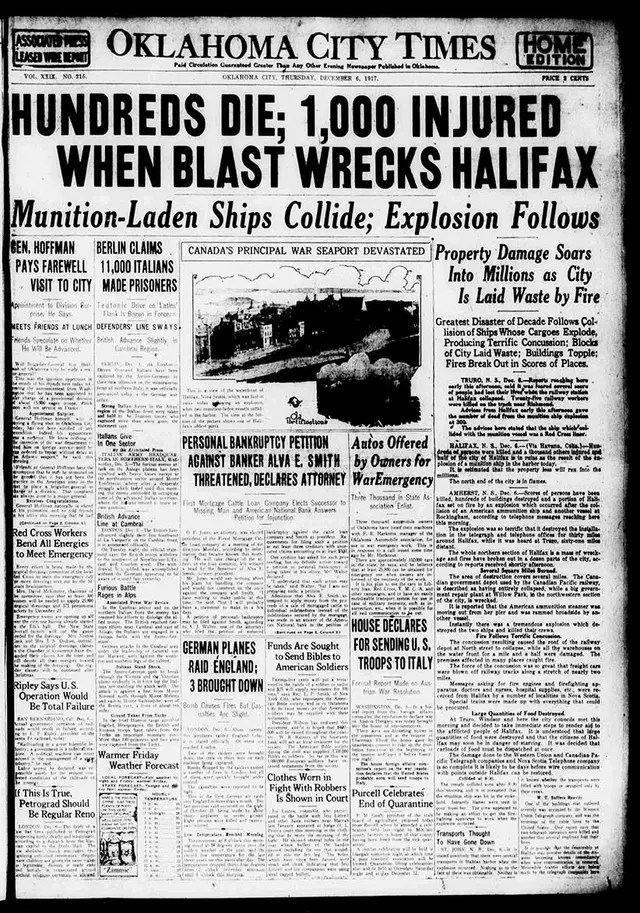

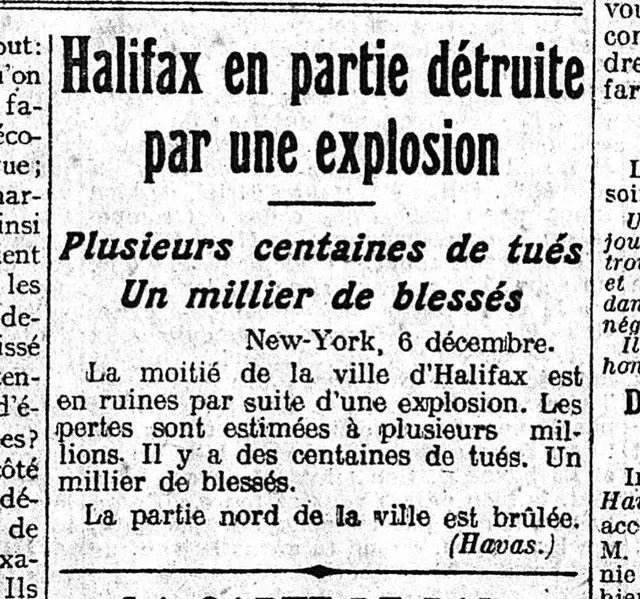

“There are many non-fiction books about the Halifax Explosion out there, but Breaking Disaster offers the unique perspective of seeing the disaster through newspaper headlines.

Katie Ingram scoured the newspapers around the world that came out at the time of the explosion. In her book she looks at what was printed versus what really happened, including rumours that were spread through inaccurate information and paranoia, as well as survival and hero stories that we still hear of today (including the story of Eric Davidson).

… I was struck by how far and wide the news of the disaster spread – Ingram includes headlines from newspapers as far away as Hawaii and Australia. I was also surprised by the strength of the rumours about the explosion being in some way related to the war.

… Breaking Disaster’s focus is on these early misconceptions, changing facts, and mistaken information. This is a book about survivors who shared their stories in those early hours and days.”

By the Author

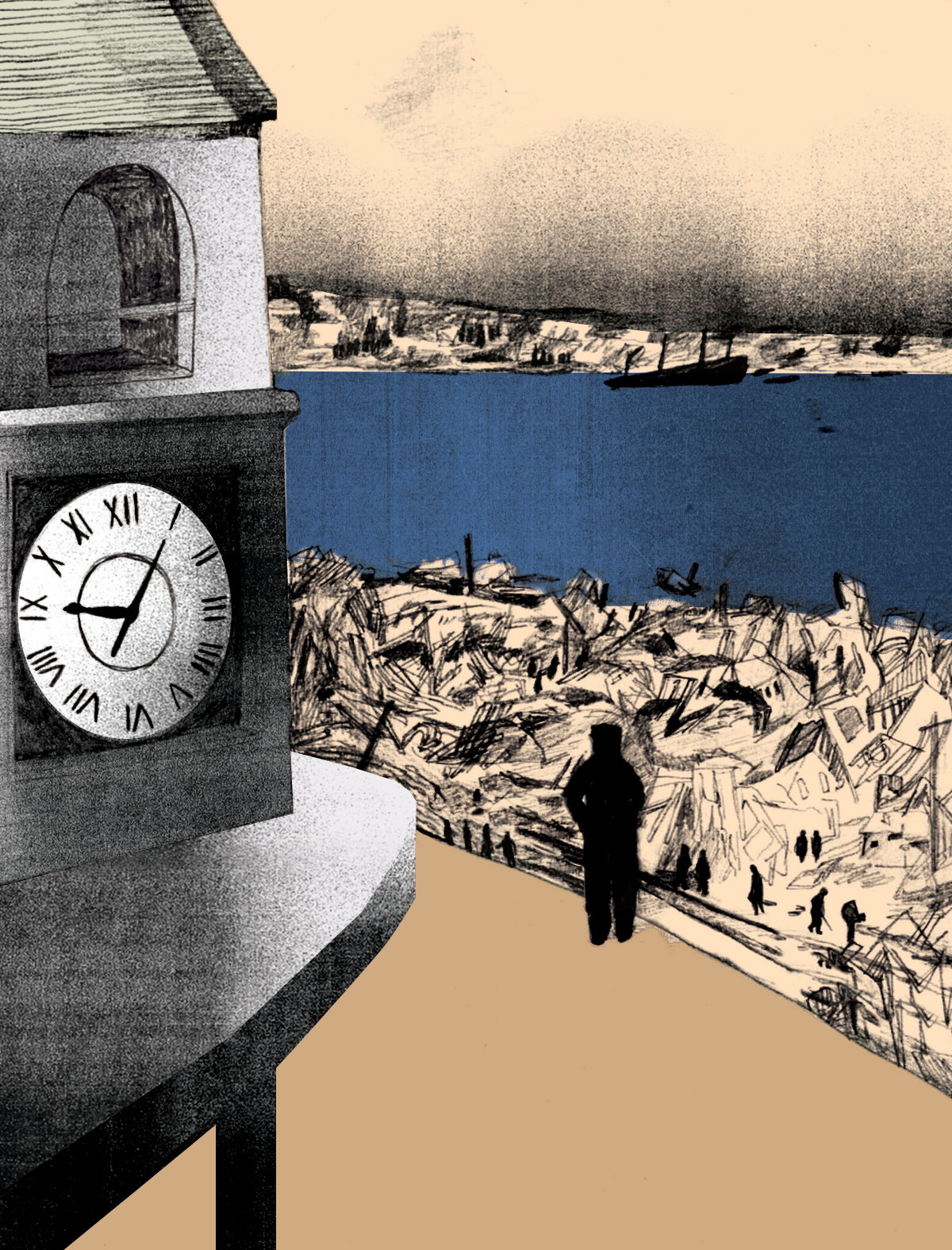

For Maclean’s: “On Dec. 6, 1917 the Imo, a Belgian Relief ship, collided with the French ship, the Mont Blanc. Shortly after 9:00 a.m., the Mont Blanc, which was carrying a large cargo of explosives, blew up. It destroyed much of the city’s north end and damaged neighbouring communities like Tuft’s Cove and Dartmouth. The effect was catastrophic.

Almost immediately, aid was rushed to Halifax as survivors and workers dug through rubble and ruins for friends and family. Over 2,000 people died and 9,000 were injured, while countless others were rendered homeless. As news broke about the explosion, newspapers from Toronto to Hawaii and France to Australia scrambled to provide readers with updated information.

Here are a few of the ways the newspapers of the world told the story of that day and its aftermath.”

For The Walrus: “On December 6, 1917, the Imo, a Belgian relief ship, accidentally struck the French ship the Mont-Blanc in the Narrows, a thin waterway between Bedford Basin and Halifax Harbour. Unbeknownst to most people in the vicinity, since the Mont-Blanc wasn’t flying the proper flag, the ship was carrying 2,300 tons of picric acid, 200 tons of TNT, ten tons of gun cotton, and thirty-five tons of benzol.

The Mont-Blanc caught fire and started drifting toward Pier 6 and the northern Halifax community of Richmond. At 9:04 a.m., the ship exploded in the largest man-made explosion before the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima.

Two thousand people died from the blast itself and from subsequent tidal waves and exposure to the elements, while another 9,000 were injured. A large section of Halifax’s north end, roughly 2.5 square kilometres, was obliterated, along with the First Nations community of Turtle Grove on the opposite side of the harbour. Other areas, including Halifax’s South End neighbourhood, parts of Dartmouth, and Africville, an African Nova Scotian community along Bedford Basin, sustained damage.

Later that morning, Toronto Daily Star readers were told Halifax was ‘wrecked,’ and hospitals were overflowing with patients. One-fourth of the city ‘lay flat,’ as flame and smoke filled the air.”

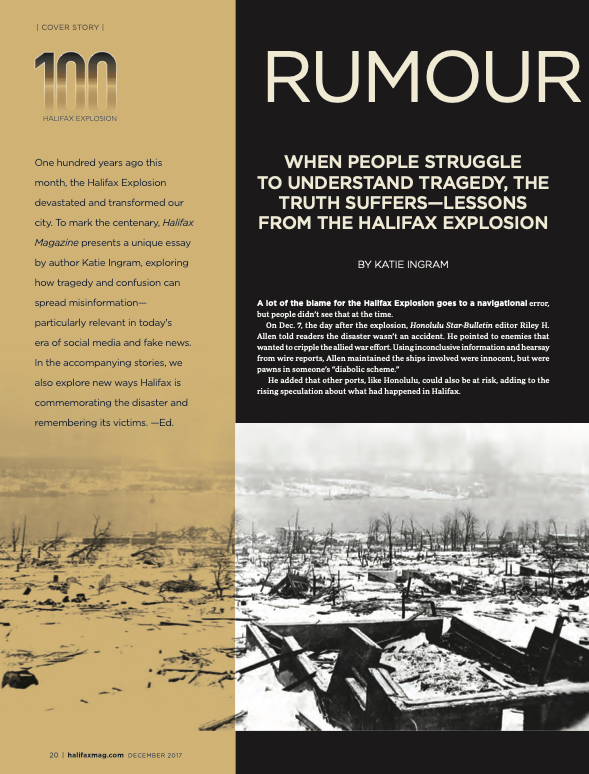

For Halifax Magazine: “A lot of the blame for the Halifax Explosion goes to a navigational error, but people didn’t see that at the time.

On Dec. 7, the day after the explosion, Honolulu Star-Bulletin editor Riley H. Allen told readers the disaster wasn’t an accident. He pointed to enemies that wanted to cripple the allied war effort. Using inconclusive information and hearsay from wire reports, Allen maintained the ships involved were innocent, but were pawns in someone’s ‘diabolic scheme.’

He added that other ports, like Honolulu, could also be at risk, adding to the rising speculation about what had happened in Halifax.

Allen didn’t have any information to verify those claims, but that didn’t stop him from making them. He wasn’t the only one to speculate, and his claims weren’t the most outlandish.

The Halifax of 1917 wasn’t much like Halifax today.

The world was at war and as one of two major Canadian East Coast ports, and the one closest to Europe, was abuzz with activity as convoys, nurses, soldiers, and relief ships traversed the harbour daily.

With the activity came the fear that the Germans would attack Halifax. With the increased traffic came extra precautions such as anti-submarine nets, but otherwise the war left Halifax untouched.

On Dec. 6, that changed.”